Vagaira groups, a type of family support mechanism, facilitate ‘successful’ internal migration amongst fishers on the East Coast of India

By Nitya Rao (N.Rao@uea.ac.uk), Professor, Gender and Development, School of Global Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, and J. D Sophia (sophia_john@rediffmail.com), Independent Researcher, Chennai, India

Marine fisheries in India is a caste-based occupation, with a social and political hierarchy in place. For those belonging to the subordinate fishing castes, excluded from decision-making processes at home, migration is an important strategy for gaining economic resources, social power and recognition as skilled and successful marine fishermen. In this pilot study, we explore the processes and mechanisms underlying the internal migration of fishers in coastal Tamil Nadu, India, and the pathways to ‘success’ both in terms of social mobility and material wellbeing. We interviewed 65 migrants, both men and women, who have moved from Rajakuppam, their village in Tamil Nadu’s Cuddalore district, to Kasimedu in the state’s capital – Chennai.

Male migration in the locality is rising, mainly as a pathway to accumulate capital for investment in mechanized fisheries. Women often lose access to fish as a result and are obliged to abandon their occupation. While they lose incomes and their contributions are invisibilised, women continue to play important roles in the social reproduction of the fishing enterprise, largely unacknowledged. In seeking to better understand gender relations in the context of rising migration amongst fisher households, we report here on the importance of marriage ties and kinship relations, brokered by senior women, on the outcomes of migration.

A range of factors from coastal erosion and natural hazards to the lack of infrastructure and poor marketing facilities in their village, have made the local fishermen look for opportunities elsewhere. They found fishers in Chennai using advanced craft, gear and engines, but importantly, earning remunerative prices for their catch. This made Chennai an attractive destination. The first migrants from Rajakuppam, however, confronted a host of institutional barriers and everyday conflicts. The Chennai fishers were Pattinavars, while those from Rajakuppam belonged to the numerically smaller and hierarchically subordinate Parvatharajakulam caste group. The Chennai fishers didn’t allow the migrants to register their boats, or join the fisher association, made them pay penalties for fishing in their waters, and engaged in several small forms of everyday harassment.

Despite these daily tensions and conflicts, the Rajakuppam settlers gradually built political connections that enabled them to receive federation boats and all government schemes and entitlements alongside local fishers. With this eligibility they formed their own association and enrolled as members in Fishermen Cooperative Societies. Alongside this, they focused on strengthening their social capital, as trust and social support were critical for overcoming the resistance they faced and achieving positive outcomes. As their children grew up, and their daughters married, they formalized a family support group known as ‘vagaira’– literally a collective of members tied together through kinship and marriage, as a form of bonding social capital. Though six vagaira groups have been formed with about 65 migrant households, we focus here on the Annamalai Vagaira, constituted by the first migrants to Chennai, to better understand its organization and contribution to their success.

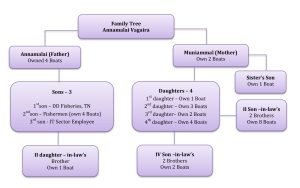

The Annamalai Vagaira is an informal family collective, constituted over a period of time, bringing together generations for a common goal. A senior woman, Muniammal, 65, wife of one of the first migrants, was central to this social organisation, negotiating with different members of the family their respective roles, contributions and entitlements. While initiated by her and her husband, the next layer of the vagaira included her seven children, both sons and daughters, and their families. Once her children were well-settled and self-sufficient, the group was further expanded. Brothers of both her sons-in-law and daughters-in-law constituted the third layer. Over time, other relatives such as her sister’s son joined the group. This vagaira group now has 13 families owning 26 boats (see Figure 1). While two of her sons are not actively engaged in fishing, her daughters’ families all now own boats and are dependent on fisheries for their livelihood.

The vagaira provides its new members financial support for investing in boats and gear. When two of Muniammal’s second son-in-law’s brothers came to Chennai, her daughter mobilised money from her siblings for them to start the fishing business. Gradually after stabilizing their business, they repaid the amount to her daughter. But it is more than money; the group continues to provide emergency cash and capital, technical knowledge, marketing support to fetch better prices and reduce losses, and conflict resolution to start and expand their business. Transparency in sharing information about their fishing assets like crafts, gear and other equipment, creates a team spirit, rather than one of competition. Rapport and trust within the vagaira is strong. It is this commitment to supporting each other through the exchange of goods, money and ideas that is perhaps one of the most important factors driving the success of the Rajakuppam fishers in Kasimedu.

While being a member of the vagaira group, each family maintains a clear division between the domestic and productive spheres. Women take family-level decisions relating to matters such as education, health, and savings, but those relating to the purchase of boats, nets, other equipment, fixing traders and auctioneers for selling their fish, are taken collectively. With practical experience, new members learn to make informed decisions, while the vagaira’s collective social capital allows for the sharing of risk, the monitoring of emergent threats and opportunities and the provisioning of moral and material support during times of crisis.

Women’s social reproduction roles are often ignored in studies of gender relations and divisions of work in the fisheries sector

The key elements that keep the group together are the strong relationships between siblings and kin, financial give-and-take, knowledge and asset sharing, collective decision-making and the exchange of suggestions/advisories. Despite these positive features, conflicts do arise, mostly related to finances and the number of boats owned. Jealousies arise among women if their monetary expectations are not met. It is usually the older women like Muniammal, who talk to the conflicting parties and help arrive at an amicable resolution. As KV, the eldest son of Muniammal, noted, “my mother is an accomplisher, and she now plays the role of an advisor to many. She helps maintain a smooth growth curve by facilitating the resolution of the small ups and downs among and between the families of our Vagaira”. The other early migrants too established family groups and are doing well in Kasimedu. These groups give hope to the migrants from Rajakuppam and provide hand-holding support if they wish to establish themselves in the sector.

Fishers from many parts of Tamil Nadu migrate to Chennai for fishing, but in the absence of a support system, during times of crisis or conflict, they see no option but to return to their home villages. Rajakuppam fishers, belonging to a homogenous but marginalised caste group, confronted many challenges by supporting each other through their family groups. This strong family cohesion played a key role in making them ‘successful’ settlers in Kasimedu. KV continued: “We were the first to become boat owners in Chennai, and we then expanded our team by constituting a family group. None of the 44 fishing villages of Cuddalore has the system of Vagaira; it is we from Rajakuppam who created, demonstrated and sustained this model. Now amongst us, there are five to six vagaira groups, each owning a minimum of ten to maximum thirty boats”.

Over the past four decades, the migrant settlers from Rajakuppam, now owning almost one-tenth of the boats operating out of Chennai harbour, their children in higher education, have achieved both economic and social mobility. They belong to the upper classes amongst fisher families, with a high standard of living, and have broken caste barriers between themselves and the dominant Pattinavars. Theirs is a story not of exploitation, but of success, despite the many challenges they faced.

At the same time, their bonds with their family groups; fellow fishers and fishing labour have also become stronger. As Muniammal clarified, “wives of boat owners, especially senior women, have played a central role in building and maintaining social ties, both within the family and vis-à-vis the wider society”. Women’s social reproduction roles are often ignored in studies of gender relations and divisions of work in the fisheries sector. The experience of vagairas, explored in this paper, makes visible women’s central roles in ensuring the success of migrant fishers’ enterprise.

Note: This article is extracted from the research paper: Rao, N., Sophia, J.D. (2023). Identity, sociality and mobility: understanding internal fisher migration along India’s east coast. Maritime Studies 22, 42 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00333-1