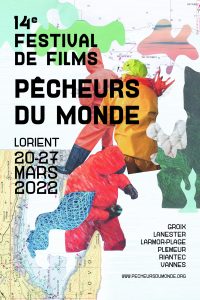

The 14th edition of the Pecheurs du Monde film festival in Lorient, France, showcased the resilient cultures of fishing communities around the world

This article is by Jacques Cherel (jacquesfran.cherel@wanadoo.fr), president of the Lorient Pêcheurs du monde (Fishers of the World) film festival

Discovering the world of fishers can be exciting and enriching. About 2,500 spectators made that discovery in Lorient, France, and in its surrounding towns from March 20 to 27 on the occasion of the 14th edition of the Pecheur du Monde (Fishers of the World) film festival. It featured the screening of 30 films, followed by discussions in the presence of directors, scientists and marine experts. The films depicted a great variety of fishing and geopolitical conditions from across the world, highlighting several common points.

Adapting to change

How fishers carry out challenging tasks at sea in conjunction with the natural elements in a magnificent but risky environment is depicted in Des Hommes à la mer (Men at Sea) by Alexandre Ruffin, which depicts fishers constantly adapting to variations of weather and economic or administrative conditions.

Bryony Stokes’s Plenty More Fish? features the creativity of the inhabitants of British Cornwall; they are taking up the challenges of tomorrow’s fishing in the face of climate change.

In The Long Coast, Ian Chenay analyzes the situation in the Northeast of the United States. Fishworkers here are engaging in alternative activities after the disappearance of cod from their coasts. The film draws out the route fisheries products take from the sea to the consumer’s plate, unknown to most people. It invites us to create a new link with the producers.

Pushing back

Across the world, imposed development projects are excluding fishers from traditional coastal waters. Blanche Bonnet’s film Bargny, quand le futur s’enfuit avec ses lendemains (Bargny, where the future runs away with its tomorrows) documents one such reality. The building of a district based on the Dubai model and a coal-fired power plant threatens to evict fisher families in Dakar, Senegal.

The films depicted a great variety of fishing and geopolitical conditions from across the world, highlighting several common points

In Xaar Yallà, Mamadou Khouma Gueye shows the sadness, dignity and revolt of the women of the port of Saint Louis, Senegal. They face the destruction of their homes due to sea level rise and the development of a new oil field that will ruin fishing activity. The inhabitants are being ‘evacuated’ to an arid area.

In the completely different setting of the Bay of Saint Brieuc in France, fishers are protesting against a wind farm project commissioned in the middle of their fishing areas. Mathilde Jounot’s film Océan 3, la voix des invisibles, la drôle de guerre (Ocean 3, the voice of the invisible, the comical war) reports on their distress and struggle. The discussion on this film was a lively affair, led by Alain Le Sann of the Collectif Pêche et Développement and a member of the film festival’s board.

Plundered resources

In Aza Kivy (Morning Star) the Malagasy filmmaker Nantenaina Lova investigates the Vezo nomadic fishermen of Tulear, Madagascar, who follow the shoals of fish southwest of the big island. A respectful relationship with the sea and its rituals, and an affirmation of the link between the ancestors and the living are expressed in a strong cultural identity, backed by bewitching music. Today, large foreign trawlers, often Chinese, are depleting the fish stocks and ruining the traditional practices of the community.

Everywhere, people of the sea are asking to be recognized, to be involved right from the beginning in the development projects along their coasts

In addition to this plunder, an industrial mining project and the building of a port threaten the coastline and the forest in the interior. The Vezo and Masikoro, whose activities are complementary, are resisting these developments. Despite repression and imprisonment during their demonstrations in the main city of Antananarivo, their determination overwhelms the filmmaker. In an interview at the festival, Nantenaina Lova makes their message known: “Leave us alone with our way of life, which despite being traditional, preserves the environment. It’s a simple fact that without the looting, this country would not be dependent on foreign aid.” The mining project is now frozen but the Vezo remain vigilant.

Struggles of the invisible

Everywhere, people of the sea are asking to be recognized, to be involved right from the beginning in the development projects along their coasts. They also question the validity of these projects: Is it really a question of meeting energy needs and remedying global warming, or rather a race for profit by ‘colonizing the sea’ after the land, as the journalist and festival jury member Catherine Le Gall says in her book, L’imposture océanique?

If it is necessary to reduce the environmental divide between humans and non-humans, we cannot ignore the colonial dimensions—read slavery and colonization—that continue through the plundering of marine and mineral resources.

The show Danser l’océan (Dancing the Ocean) put on by Betty Tchomanga and Mackenzy at the fishing port in front of more than 200 people drew attention to this theme.

Biodiversity preservation

Au nom de la mer (In the Name of the Sea) by Caroline and Jerôme Espla alerts us to the seriousness of the ecological disaster in the Mediterranean. The Lorient festival initiated a discussion on ‘Fishing of the Future’ by proposing a first debate led by Agathe Le Gallic, a graduate in maritime law, on how to reduce the impact of plastics on water quality.

It explored several critical questions. What solutions do the industrialists offer? What initiatives are possible for the sake of fishers’ interests? What do high school and college students think?

David Constantin’s Grat Lamer Pintir Lesiel is a moving plea from fishers, following an oil spill. It is a rare post-disaster story about the inhabitants of Mauritius struggling to regain their livelihood and their link with the sea.

Jury awards

The festival proposed a competition of seven feature films and four short films from seven different countries. The jury of professionals from the film and fishing industries and the other jury of young students of maritime and classical studies were unanimous in their choice. The film Ostrov, the Lost Island by Svetlana Rodina and Laurent Stoop won the Feature Film Award and the Audience Award. The film intricately explores the situation of poor Russian fishers on an island in the Caspian Sea, echoing the current events in Ukraine and Russia.

The award for best short film went to Xaar Yalla by Mamadou Khouma Gueye. The jurors were moved by the message of the women driven from their homes.

Azadeh Bizarti’s Iranian film, The People of Water, is a tribute to the women who have to fish to survive in southern Iran. It received the Chandrika Sharma Award for a film highlighting the role of women in fishing.

A maritime culture

A special mention from the professional jury was awarded to Iorram (Boat Song) by Alastair Cole. It shows how fishing is part of the culture of a country, in this case, the Hebrides in Scotland.

A whole section of the festival highlighted the heritage of the people of the sea. Mémoire en conserve (Canned memory) by Lizza Le Tonquer and Clémentine Le Moigne recalls the work of women in sardine canneries in Brittany, France. Alain Pichon highlighted the image of the region’s fishers through documentary films of the 1930s. He shows the importance of men and women in the dynamics of Brittany’s coast, using archive films from the Cinémathèque de Bretagne.

A whole section of the festival highlighted the heritage of the people of the sea

The films in the festival constituted a testimonial to the world of fishers developing a specific culture of the sea and the coast, simultaneously participating in the wider culture of society at large. New initiatives underline the link between sea and men as demonstrated in the two-part show at the fishing port.

A film-concert titled La Voix des Océans showed images of plankton by Pierre Mollo and Jean Yves Collet, with music by Antonio Santana. It was followed by a dance performance by Betty Tchomanga and Mackenzy called Danser l’Océan. Another concert in Ploemeur, titled La part des singes, brought together more than 150 people to watch Yannick Charles’ film on the fishing boat captains of Lorient. These were among the high points of the festival that immersed the public in the world of fishworkers.

Livelihood, the thrust

In the film Fish Eye by Iranian director Amin Behroozzadeh, the world looks like an industrial seiner, roaming the Indian Ocean in search of tuna. Its crew is made up of Africans under the control of white men. The boredom of the men who have difficulty communicating with their families, the agony of the fish, the gigantic size of the nets, the false appearances of understanding… All these images provoke contradictory reactions, turning the film into a metaphorical tale rather than a documentary. It questions the meaning of a productivist economic system cut off from life.

These were among the high points of the festival that immersed the public in the world of fishworkers

As the effects of the Russia-Ukraine conflict remind us, there is an urgent need today to respond to increasing food insecurity, the effects of climate change, growing drought and unpredictably violent changes in weather conditions. The role of artisanal fishers in nutrition, poverty eradication and the sustainable use of natural resources is fundamental. The Lorient festival has taken up the campaign of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) for the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture (IYAFA 2022).

It is claimed that fishing is very important because it contributes to feeding the population, but in reality, the opposite is true. If we continue to reduce the fleets on the Breton coast, we will have to import even more fish from Africa, Latin America and Asia, which will be taken away from the populations of these continents. Everywhere, the peoples of the seas are anxious about their future. The trust between the State and the people must be re-established.

The commitment of Malagasy and African directors such as Nantenaina Lova and Mamadou Khouma Gueye is worth noting. They organize screenings and citizen assemblies for debate in villages and shanty towns. They give a voice and a positive image to those ‘neglected and despised’ by the mainstream system. The Festival des Pêcheurs du Monde in Lorient helps to highlight these struggles.

Saving the oceans requires reflection on the value of the work of fishing communities, their relationship with the sea, and the human relations between the North and the South. These are some of the themes that the next editions of the Festival Pecheurs du Monde hope to present to the public.

For more

14th Edition of the World Fishermen Film Festival from March 20 to 27, 2022

https://www.pecheursdumonde.org/

To Memory, Poetry…and the Future

https://www.icsf.net/samudra/france-film-festival-to-memory-poetry-and-the-future/

A Fisheye View

https://www.icsf.net/samudra/a-fisheye-view-2/

Hope, Despair, Courage

https://www.icsf.net/samudra/hope-despair-courage/